Marc Levin and David Paul Kuhn Look Back on the 'Hard Hat Riot'

Kuhn's book is now a documentary, directed by Levin, that will premiere Sept. 30 on American Experience

There was a time before social media, before America’s culture wars, and before the deep divisions we see around us now when American society was even more deeply riven, and it wasn’t so long ago. The 1960s was a time of great upheaval, thanks in large part to the Vietnam War and the rebellion of young people against an establishment they viewed with suspicion, if not downright hostility.

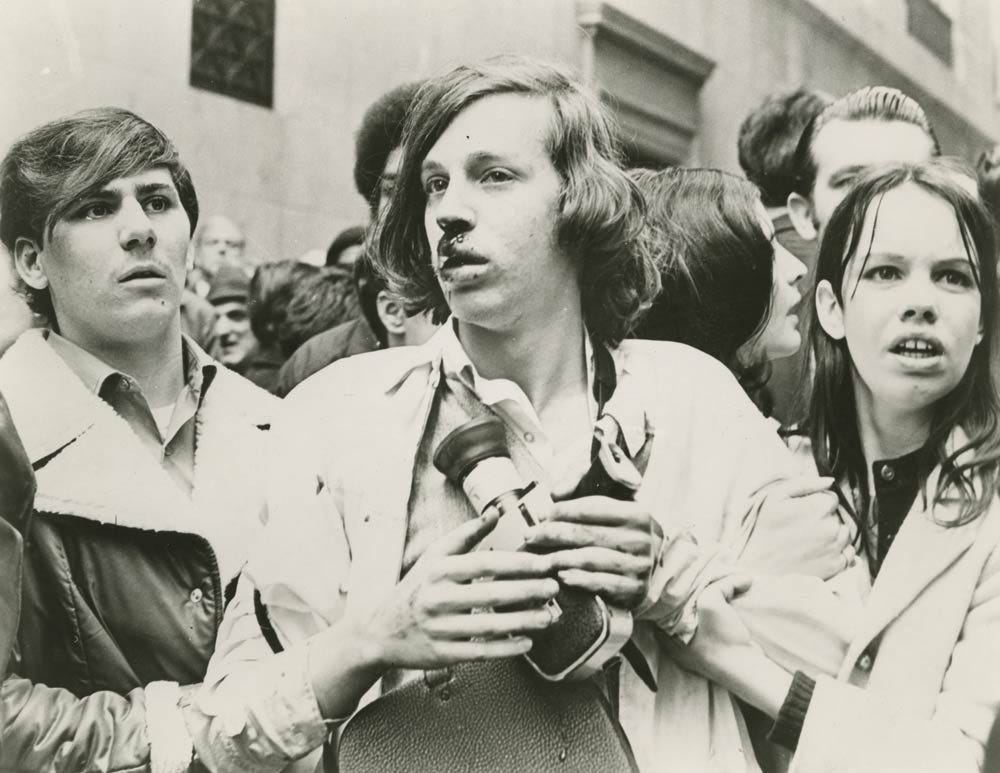

It was against this backdrop that the dramatic events of May 8, 1970, unfolded. The subject of David Paul Kuhn’s book The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution, that day saw a watershed confrontation explode when construction workers surged into the streets of Manhattan during an anti-war demonstration. The workers — the “hardhats” of the book’s title — were angered by such protests, and resentful of what they viewed as privileged youth shirking their patriotic duty and desecrating the American flag. Many were military veterans as well as having forebears who had defended American values in World War II and, in the 1950s, served in the Korean War.

(Photo: ‘Hardhat Riot.’ Provided)

For their part, the protestors weren’t just demonstrating against the Vietnam War on that occasion. Only a few days before, on May 4, National Guardsmen had opened fire on demonstrators at Kent State, killing four students. One of them, Jeffrey Miller, hailed from Plainview, a hamlet of Oyster Bay, New York — a geographical happenstance that may well have made the day’s protest feel that much more personal to the anti-war demonstrators.

Kuhn’s book has been turned into a documentary by Marc Levin, director of features like Brooklyn Babylon (2001) and docs like One Nation Under Stress (2019), Class Divide (2015), Protocols of Zion (2005), and last year’s investigation into right-wing domestic terrorist Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, An American Bombing: The Road to April 19.

Titled Hard Hat Riot and due to be featured on PBS’ American Experience, Levin’s new documentary takes an incisive, comprehensive look at the clash, and traces its aftermath to today’s politics. As the film’s tagline has it, the colossal street fight was “The clash… that swung blue collars to the right.”

Levin and Kuhn offered their behind-the-scenes perspectives in a recent interview.

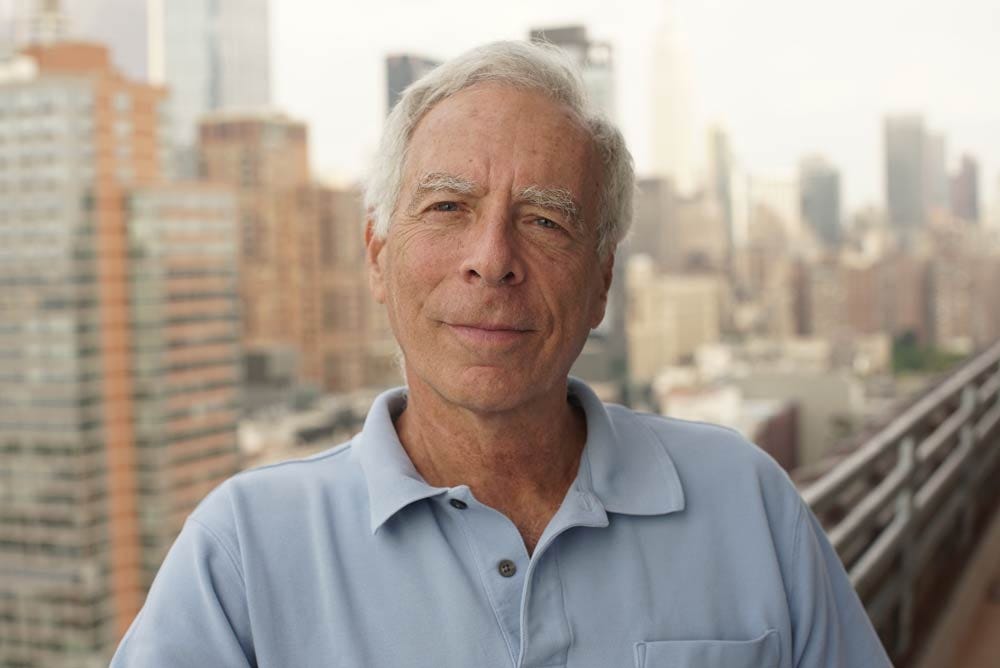

(Photo: Author David Paul Kuhn. Provided)

Kilian Melloy: Thanks for taking the time to speak to me today. Let me start off by noticing that this documentary feels very relevant. We’ve been heading in this direction for a while now, so was the situation in our society something that caused you to look back on the past and reflect on where things seem to be going?

Marc Levin: I will let David start, since he started the research before I got involved.

David Paul Kuhn: This was in my first book, which came out in the Obama era, but it was a page and a half. The hard hat riot was an anecdote in history. Then Trump became a serious candidate in 2016, and I knew I wanted to write another book, but one that had more narrative. I knew right away it was this riot. There was a legal battle, so I had great hopes that because of the rules of discovery there would be documents, because those documents are critical to creating a real narrative. It’s very hard with historic events. To be sure, the present troubles led me to want to reach back for this lesson of history.

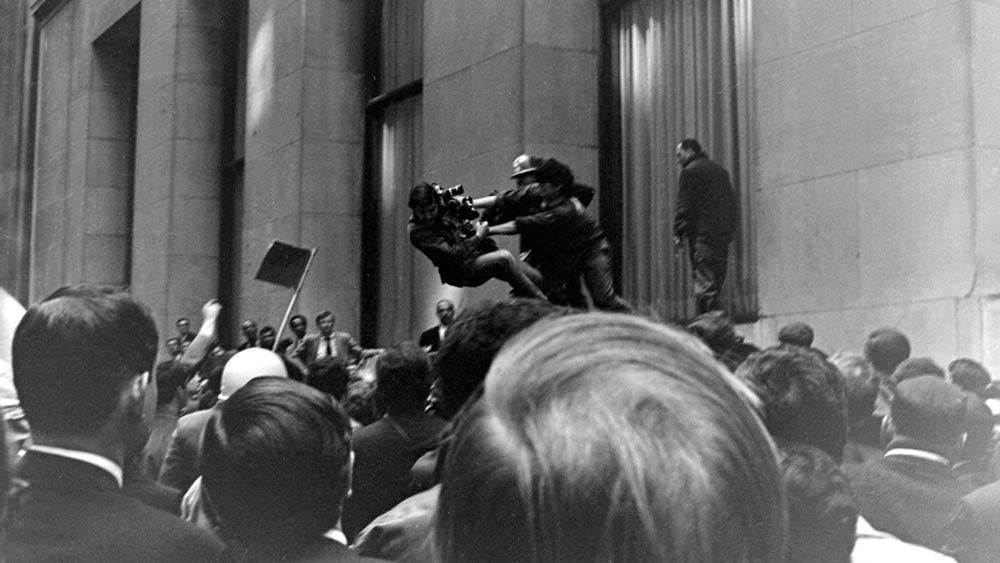

Marc Levin: I think there were two things: One, when I first saw the footage that David unearthed through his freedom of information request and got the police surveillance footage that had not been seen before, I was stunned. It immediately reminded me of January 6, because it was [that] kind of hand-to-hand combat — people wrestling and hitting each other in the street.

I had done a film before this for HBO, An American Bombing, which looked all the way back to the early ’80s and the rise of the kind of militant right-wing fanaticism that was the world that Timothy McVeigh stewed in before he committed what is the worst act of domestic terrorism in American history. So those two things converged in my own interest, and then I read David’s book and found it a fascinating insight into a question that pundits and academics were asking: How did the Democrats lose the working class? What happened? In this microcosm, and in David’s book and in our documentary, I think you find the seeds of the answer to that question.

Kilian Melloy: David, in the writing of your book you must have talked to quite a few people about that riot. You are a producer of the film, so did that background help you when it came to the production of the documentary?

David Paul Kuhn: For sure. Mark and another lead producer, Daphne [Pinkerson], were so generous about letting me learn about filmmaking along the way, and there is no doubt that the book informed who we chose to interview in person. Obviously, you have to think about who will be good on camera, who’s still with us [and] actually has the energy, the verve [to be interviewed], because this was over a half century ago at this point.

Unlike with a book, film allows you to feel an event — to be enveloped in a multisensory way. You try to do that in prose; I tried to bring up smells and the sense of fear, but you just can’t create [in text] what a film can. The context of the research definitely informs who I thought would be the best interviews. Without a doubt, seeing them on camera is a very different than holding a tape recorder next to a person. The camera brings out their spirit.

(Photo: Marc Levin. Provided)

Kilian Melloy: This is a very even-handed film. Including people from different sides of this riot — hard hats and the protesters alike — gives us more of an understanding of what happened. But, Marc, did you find it was particularly difficult to get people to open up about their role in the day and now they feel about it now?

Marc Levin: Well, look, the trick of documentary filmmaking is making people feel comfortable, to confide in you, to be honest, to be relaxed. Finding some of the participants on the hardhat side was key, and developing a relationship where they trust us. I was up front with the people we talked to. I was in New York City that day. I was a 19-year-old kid who dropped out of Wesleyan and was working as an apprentice for the Maysles [Brothers] on Gimme Shelter. I was up at 1697 Broadway, at their shop, listening on WINS Radio because I was interested to find out if Willis Reed was going to play in the NBA finals that night [with the Knicks] against the Lakers, and all of a sudden this bulletin comes on that there’s this disturbance down on Wall Street, people beating each other up. I could have well been down there, so I had to be honest about my own past and where I was from. But once we got that sense of trust, everybody was very willing to go back in time. I was amazed by some of their memories, because it’s somewhat of a fog in my mind.

So much work has been done about the ’60s, about the early ’70s, and so much of it from the counterculture perspective, the anti-war perspective, the civil rights perspective, women’s rights, environmental rights. So, looking at the other side, as David’s book does, and getting [people] to not only talk about their role in the riot, but who they were, where they grew up, you know, what they felt about the war — I mean, a lot of a lot of people were against the war, or felt the war, especially since the Tet Offensive, was unwinnable and a tragic mistake. But they supported the troops, they supported the flag, and they were from a culture that felt offended by some of the extremism of the anti-war movement.

I hated Nixon with such fervor when I was 19 years old, but making the film, I got a different perspective on him as somebody who grew up working class, who never got into an Ivy League school, who felt rejected by the Eastern elite establishment, and how he had this intuition to connect with not just the blue bloods, but the blue collar. That was an eye opener.

(Photo: ‘Hard Hat Riot.’ Provided)

Kilian Melloy: Today we have to reckon with social media which, especially recently, seems even more prone to create violence and disarray.

David Paul Kuhn: I was so steeped in the ’60s and ’70s to write this book, because, listen, that’s not my generation, so you’re hyper paranoid you’re going to miss something, you’re going to get something wrong. So, I read copious amounts, did immense amounts of research, and I think about that all the time: What if social media was around in 1970, 1971, when the left wing radicalized? There’s a far right in this era that’s radicalizing. I know that it got much worse in that era than in our own, and it lends perspective that America can recover and can heal. But I often think, “What if social media had been there as gasoline on that fire?” You always worry that whatever present troubles we think are terrible, they’re a prologue to worse. So, I think it’s a very deep and concerning question, the impact of technology heightening these divides that were worse in the era of our film and my book, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be worse than that [today].

Kilian Melloy: Marc, what are your feelings?

Marc Levin: I think what’s missing so much with social media [is] we lose the eyeball-to-eyeball contact, the mano a mano, the human contact. It’s irreplaceable, [as is] finding venues where you can, face to face, deal with people who you may ideologically differ with, but there is some common ground. I’ve often reflected on how that night of May 8, 1970, I ended up in an Irish bar on the Upper West Side with a lot of working-class guys, and we were buying each other drinks and hugging each other when the Knicks won the NBA championship. It was like, “One of those guys might have bashed my head only six or seven hours ago, had I been down there!” But [now] we’re so missing those opportunities of coming together, even though we differ on political ideologies and philosophies, and that is scary. And that is part of this technology that is virtual, instead of real human contact.

Kilian Melloy: May I ask each of you for a thumbnail of prospective projects, or projects you’ve already got going, for the future that we might look out for?

David Paul Kuhn: I got a few things in the hopper, but they’re not quite formed enough where I’m ready to talk about that. [Laughing] I’m passing the buck to Marc.

Marc Levin: Well, I’ve got another film I’m finishing right now, called Workers of Art on the largest philanthropic effort to employ and support artists coming out of the COVID crisis here in New York, and working on a major special on the 25th anniversary of 9/11 for next September 11.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Hard Hat Riot will premiere on American Experience on September 30.